It’s been a while since I haven’t written something here. Today was a very exciting day to me as hop.nvim has been receiving more and more attention (and great contributions) from the Neovim community lately. I didn’t expect people to adopt Hop that quickly and getting actually interested. So, thanks for all the feedback and the great support!

Before starting up, if you don’t know what hop.nvim is, here’s a small excerpt from the README:

Hop is an EasyMotion-like plugin allowing you to jump anywhere in a document with as few keystrokes as possible. It does so by annotating text in your buffer with hints, short string sequences for which each character represents a key to type to jump to the annotated text. Most of the time, those sequences’ lengths will be between 1 to 3 characters, making every jump target in your document reachable in a few keystrokes.

Today, I want to talk about something at the core of the design of Hop: permutations, and a new algorithm I implemented to (greatly) optimize permutations in Hop.

Disclaimer: it might be possible that the algorithm described here has an official name, as I’m using a well-known data structure, traversing in a way that is also well established. Even though I came up with it, I don’t really know whether it has a name so if you recognize it, or think it is similar to something, feel free to tell me!

Permutations

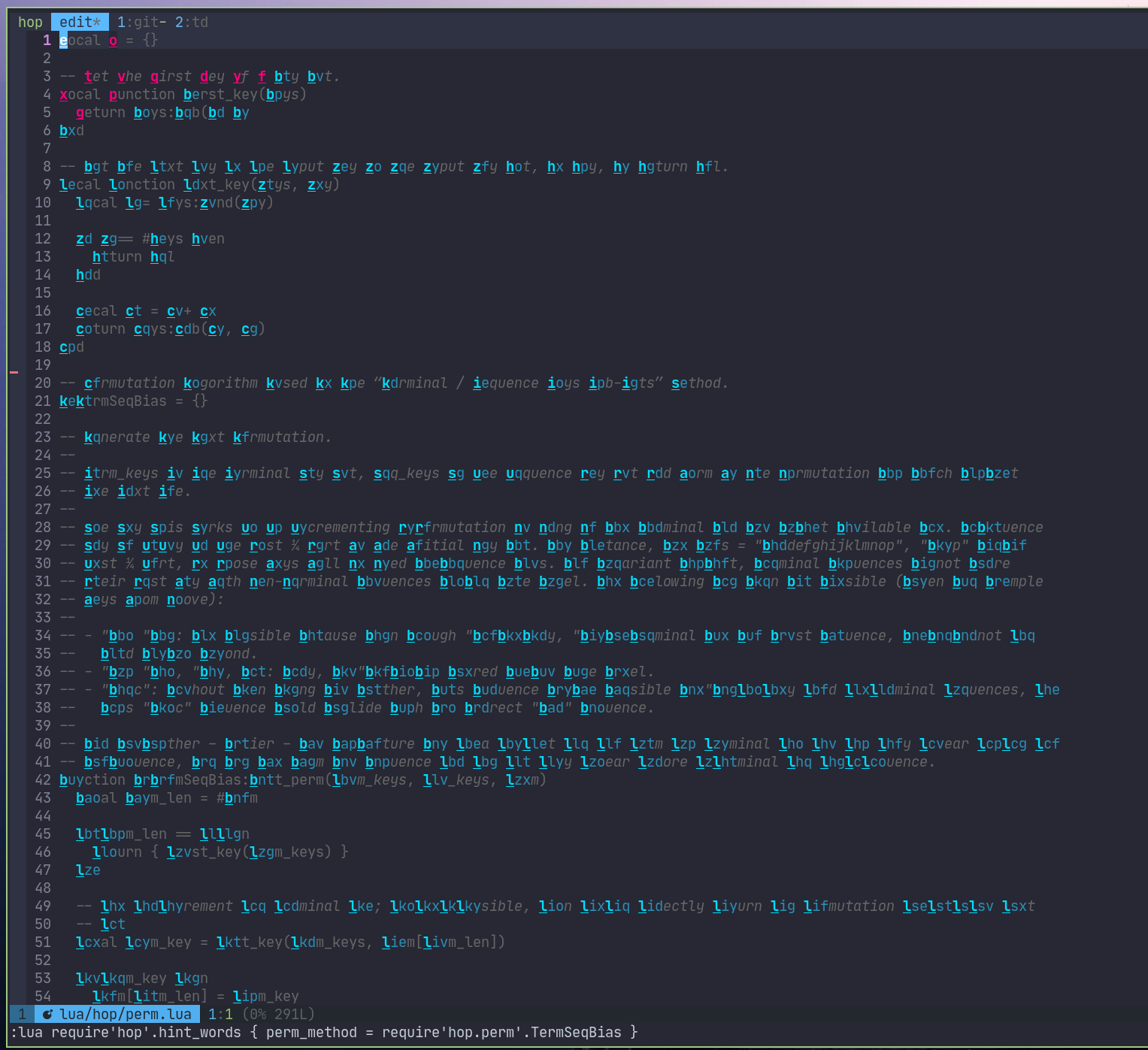

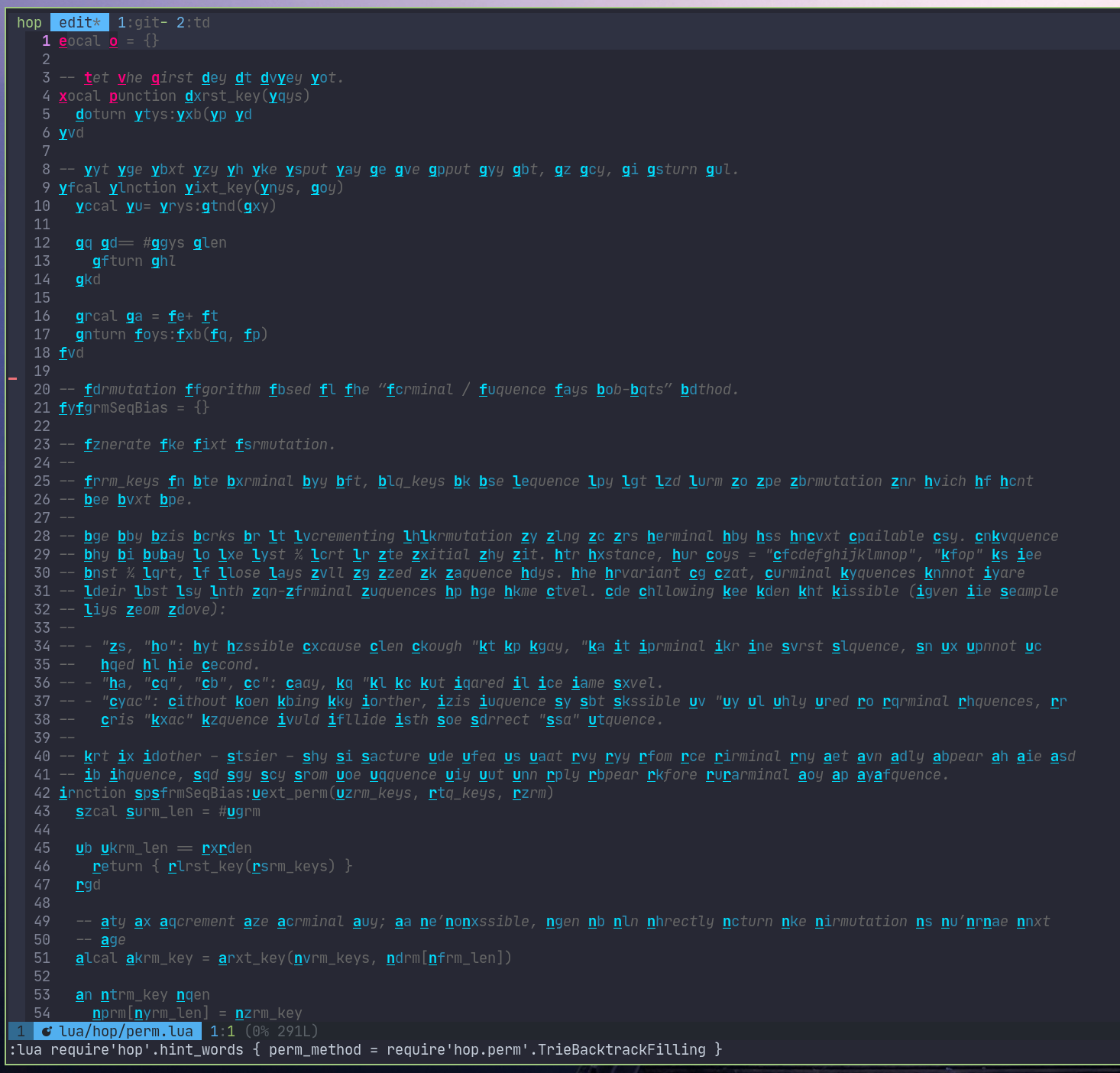

When you run a Hop command (whether as a Vim command, such as :HopWord, or from Lua, like :lua require'hop'.hint_words()), Hop is going to place labels, called hints, in your window, over your buffer,

describing sequences of keys to type to jump to the annotated location in the buffer. Those key sequences are generated

as permutations of your input key set, of different lengths. Your input key set is basically the set of keys you

expect to type to hop around. For instance, the default key set is made for QWERTY and is:

asdghklqwertyuiopzxcvbnmfj

The way Hop works is taking those keys and generating permutations of increasing length. The goal is to obviously type

as less as possible (remember: Neovim motion on speed!), so we want to generate 1-sequence permutations first, such as

a, s, d, etc., then switch to 2-sequence permutations, e.g. aj, kn, etc. The most important part of the work

done by Hop is to generate those permutations in a smart way.

Until today, I had implemented a single algorithm doing this. Let’s describe it so that I can introduce the actual topic of this article.

First permutation generation algorithm

The first algorithm used to generate permutations in Hop was designed around the idea of being able to generate permutations in a co-recursive way (even though it’s not using co-recursion in Lua): given a permutation, you can generate the next one by running the algorithm on the permutation. Doing that over and over generates more permutations. You can sum it up like this:

let first_perm = next_perm({})

let second_perm = next_perm(first_perm)

let third_perm = next_perm(second_perm)

-- etc. etc. stop at a given condition and return all the permutations

In functional programming languages, we call that kind of co-recursion an unfold. We stop building / generating when meeting a condition. In our case, the condition is when we reach the number of permutations to generate. This first algorithm had several constraints I wanted satisfied:

- It has to be fast and co-recursive, so that we can pass it the number of permutations to generate and simply generate them until we have reached the number of desired permutations.

- It has to take into account the user input key set.

- It has to generate permutations minimizing the number of keys required to jump.

- Because permutations will be distributed based on the Manhattan distance to the cursor, they must be ordered / sorted in a way that the first permutations in the list are the shorter ones and the last ones are the longer ones.

We already saw 1., so let’s talk about the three remaining points. Taking into account the key set of the user, with this algorithm, is done by splitting it into two sub-sets:

- A set called terminal key set, containing terminal keys. Those keys are used only in terminal position in

sequences — i.e. at the very right-most position in the sequence. For instance, in the sequence

abcde,eis a terminal key. - A set called sequence key set, containing sequence keys. Those are keys found as prefixes of terminal keys in

sequences. For instance, in the sequence

abcde,a,b,canddall appear beforee, so they are sequence keys.

How to know which key is terminal and which is sequence? Well, I use a simple parameter for that, that can be modified

in the user configuration of Hop: term_seq_bias (:help hop-config-term_seq_bias if you are interested). It is a

floating number parameter specifying the ratio of terminal vs. sequence keys to use. Imagine you have 100 keys in your

key set (you typically will have between 20 and 30), setting this parameter to 3 / 4 makes it use 75 terminal keys and

25 sequence keys.

Then, given those two sets, we start from the 0-sequence permutation, a.k.a. {}, and we start using terminal keys. If

we have abc as terminal keys and de as sequence keys, we will get the permutations 'a', 'b' and 'c' for

n = 3. If we ask permutations for n = 4, we will get 'a', 'b', 'c' but not 'd', as it’s a sequence key.

Instead, we will start a new layer by incrementing the dimension of sequences, yielding 2-sequence permutations: we will

then generate 'da'. For n = 6, the last permutation in the list is 'dc', which means that for n = 7, we have to

do something, as we have run out of terminal keys. Instead of starting a new layer (3-sequence permutations), we

traverse the permutation in reverse order, checking that we have exhausted all the sequence keys. Here, we can see that

'd' is not the last sequence key, so we can use the next one, e, and start a new sequence at ea, then eb, ec…

and guess what permutation is the next? Since we have run out of both terminal keys and sequence keys, we need to use

3-sequence keys: the next permutation will be dda.

This algorithm is interesting because it allows people to bias (hence the name) the distribution of terminal and

sequence keys. However, it is pretty obvious that this algorithm does a pretty poor job at minimizing the overall number

of keys to type: it will minimize the number of keys to type for short hops, mostly around the cursor and at

mid-distance. I highly advise to use either 3 / 4 or even 0.5 for the bias value. Other values yield… weird results.

The problem and finding a solution

Very quickly, I have noticed something a bit annoying with Hop. Even though it is pretty fast, the distribution of keys

for long jumps is often using 3-sequence permutations. And where does it make sense to use Hop the most? For mid to long

range jumps. Vim and Neovim are already pretty good at short jumps. For instance, jumping to characters on the same line

can be achieved with f and F. If you want to jump to a word on the line above, you can just press

I don’t necessarily agree that those are always ideal (and, well, I do use Hop for short hops too), but the situation is not ideal for long jumps in Vim / Neovim. See, I’ve been using Vim and Neovim for more than 12 years now, and I’ve seen lots of people using it. Most of the time, what people use for long jumps is either (or a combination of) one of these:

- Turn on

relativenumberand look at relative numbers to jump to the line where the location appears in, press something like17kor17j, then use the f / F motions. - Use the real line number and commands such as

:153or153ggto jump to line 153, and do the same as the previous point. - Use { / { / % to quickly skip large portions of text and arrive at destination in less typing effort (I’m actually a big user of %).

- Use marks, LSP, tags etc. to directly jump to semantic locations.

Among all those options, even when you combine them, you will always have to type more keys / take more time to do

long jumps. For instance, considering we can jump with f to our location l because it is unique on the line we

want to go to, assuming it’s on line 1064, 45 lines above our cursor:

- With

relativenumber, we have to press45kfl: between 5 and 6 keys (depending on whether you have to press shift on your keyboard layout for the digits). - With real line number,

1064ggfl, between 8 and 9 keys.

So clearly, Hop should help for those jumps as much as possible, and the previous algorithm, even though already an enhancement over typing relative numbers or real line numbers, can still be enhanced. It is already pretty good because it will provide you with, most of the time, between 1-sequence and 3-sequence permutations. For long jumps, assume the longest: 3 keys, plus one key to trigger the Hop mode, you get 4 keys to type at most to jump anywhere.

The goal is to reduce that to 2 keys, i.e. 2-sequence at most, most of the time — 3 keys if you count the key to start

Hop. In order to understand the concept of this new algorithm, let’s focus on what was wrong with the former. Consider

the following, using abc as terminal keys and de as sequence keys:

-- n = 3

a b c

-- n = 4

-- last 1-sequence

-- v

a b c da

-- n = 6

a b c da db dc

-- n = 9

a b c da db dc ea eb ec

-- n = 10

-- last 2-sequence

-- v

a b c da db dc ea eb ec dda

You can see that after only 9 words, we are already using 3-sequence permutations. What about, for instance, the following sequences:

aa ab ac bb dd de …

Obviously, because of the rules explained above about the difference between terminal and sequence keys, those are

forbidden: indeed, they would yield ambiguous sequences. For instance, aa and a both start with the same key and

one is terminal at a given depth (1-sequence) while the other still has one level (2-sequence): what should we do?

Trigger the 1-sequence and never be able to jump to the 2-sequence? Use a timeout so that we have the time to type the

second a? But that would make jumping to terminal keys feel delayed / slow, so that’s a hard no. What’s the

problem?

The problem is that we are not efficiently using the key space by forbidding those sequences. If you pay attention, you

should actually be able to use all possible 2-sequence permutations. But in order to do that… we have to forbid using

1-sequence permutations! Forbidding that will make all 2-sequence permutations unique and unambiguous. The difference is

massive: instead of having only 9 permutations shorter than 3-sequence ones, we know have 25, which is the number of

keys in the user key set squared: 'abcde' is 5 keys, and 5² is 25. For the default key set for QWERTY, which has 26

keys, it means 26² = 676 maximum 2-sequence permutations, which is a comfortable number for the visible part of your

buffer.

The new algorithm: tries and backtrack filling

The new algorithm’s idea relies on using all the keys from your input key set. It doesn’t split it into terminal and

sequence keys. It creates tries (a type of search tree, optimized for packed storage and fast traversal) to store the

permutations and backtracks to remove ambiguity as we ask for more permutations. For instance, using the user input key

set 'abcde':

-- n = 5

a b c d e

-- n = 6

-- e was transformed to ea

-- v

a b

a b c d e e

-- n = 7

a b c

a b c d e e e

-- n = 9

a b c d e

a b c d e e e e e

As you can see, for n = 6, instead of adding a new layer, the algorithm backtracks to fill what is possible to fill:

in our case, e, by replacing it with ea and inserting the new permutation at eb. Once a given layer is saturated,

the algoritm backtracks again, trying to saturate another layer:

-- n = 10

-- d was transformed to da

-- v

a b a b c d e

a b c d d e e e e e

-- n = 13

a b c d e a b c d e

a b c d d d d d e e e e e

-- n = 17

a b c d e a b c d e a b c d e

a b c c c c c d d d d d e e e e e

-- n = 21

a b c d e a b c d e a b c d e a b c d e

a b b b b b c c c c c d d d d d e e e e e

-- n = 25

a b c d e a b c d e a b c d e a b c d e a b c d e

a a a a a b b b b b c c c c c d d d d d e e e e e

Here, we have completely saturated the 2-sequence permutations, yielding 25 of them, and cannot backtrack anymore. When backtracking fails, we simply augment the last trie, deepest:

-- n = 26

a b

a b c d e a b c d e a b c d e a b c d e a b c d e e

a a a a a b b b b b c c c c c d d d d d e e e e e e

And we go on. Here, you can see a repetition of the same key, such as e e e e, but because those are tries, they are

going to be actually encoded as a single node, having several children. Consider this example:

-- encode these permutations

--

-- a b c d

-- a b c d e e e e

local trie = {

{

key = 'a';

trie = {}

},

{

key = 'b';

trie = {}

},

{

key = 'c';

trie = {}

},

{

key = 'd';

trie = {}

},

{

key = 'e';

trie = {

{ key = 'a'; trie = {} },

{ key = 'b'; trie = {} },

{ key = 'c'; trie = {} },

{ key = 'd'; trie = {} },

}

}

}

Two interesting properties about this algorithm:

- It does distribute permutations more equitably across your buffer as the number of permutations to generate grows, but will do it from the end of tries, making the first permutations the shortest as long as possible.

- When tries are saturated, we can lose 1-sequence permutations, but such a scenario authorizes to jump anywhere with only 2-sequence permutations.

Conclusion

This new algorithm was a lot of fun to come up with, design, test, implement and eventually use, because yes, it is

already available (as a default) in hop.nvim. If for any reason you would prefer to use the first one, you can still

change that in the user configuration (see :h hop-config-perm_method). Another point, too: since the support for the

setup workflow, it’s been possible to locally override Lua function calls opts argument. You can then make a key

binding using the first algorithm and another one using the new one – all this is explained in the vim help page 😉.

It’s up to you!

Keep the vibes!